Introduction:

Born

in the USA

*

*http://peristats.modimes.org/ PeriStats provides free access to

US, state, city, and county maternal & infant health data.

This books

focus is fundamentally on health, normality and wellness

and

promotes an evidence-based, less interventional philosophy of care rooted in the

concept that in most women birth is not a disease, but a natural event normally

calling for little intervention.

This book addresses the pregnant

woman's changing situation at the third trimester of pregnancy, during labor and

birth, and through the early weeks after birth. The chapters discuss various

issues of obstetric management drawn from obstetrical textbooks, journals, and

research data in chronological order, as you would encounter them. When you

understand what is happening in labor and birth, you will recognize each

stage as it comes and feel more confident about trying different ways of

coping. As you learn your own personal strengths and resources for labor and

birth, you will learn to trust your body and the energy of the birth process.

Over the

course of the 20th century as a the result of an increased standard of living --

hygiene, education, improved nutrition, appropriate access to medical care when

needed and the safety net of social programs combined with wide-spread

availability of effective contraception has led to a great improvement in

maternal-child health.

Advances

-- Caesarean section among them, have made labor and birth safer and are to be

welcomed as the valuable interventions that have contributed to the relative

safety of modern childbirth. Pain management options for the woman in labor have

changed dramatically over the last decade. The shift from regional anesthesia

with significant motor-blockade during labor, where the woman is a passive

participant during the labor and birth, to a collaborative approach for pain

management, where the woman becomes an active participant, has resulted in a new

philosophy of analgesia for labor and birth.

But today these very medical and surgical procedures originally intended to

treat life-threatening complications are often routinely used on healthy women

with normal pregnancies, without having been proven more effective than non-low

interventional physiological management.

We forget that there is a purpose to labor and birth and that purpose is a baby;

a finite product of conception that is profoundly affected for better or worse

by all that ensues during pregnancy, labor and birth. Current medical research

and reams of clinical evidence shows that these experiences create chemical

pathways in baby’s central nervous system that become the physiological

foundation of life-long thought patterns, emotional feelings and

behavior.

Birth is also a

developmental process for the woman, the way she feels about her ability to

master this life event can have profound effects on the birth outcome. How a

woman experiences labor and birth affects her mothering in the first few weeks

after birth. How she feels about her experience may affect her relationship

with her baby.

The benefits of non-low interventional physiologically-based care for healthy

women with normal pregnancies and interventive obstetrical care for high-risk

complicated pregnancies has been amply documented in

current research-based medical literature as well as

in maternal-infant statistics (Johanson,

Newburn, and Macfarlane, 2002).

Non-low interventional physiologically-based care is cost-effective and psychologically sound

and has always been strongly

associated with low rates of mortality and morbidity and the long-term

well-being of mothers and babies (Johanson,

Newburn, and Macfarlane, 2002).

Historical Perspective

Up until the middle of the 18th century, birth in the United State was largely a

social event called confinement. Birth was at home, with a midwife, or an

experienced mother. These women

nurtured the philosophy, principles or techniques of physiological management of

birth. These physiological methods included time, patience with the natural ebb

and flow of labor, continuity of care with one-on-one social and emotional

support, the full time presence of the primary caregiver during labor,

an upright and mobile mother during labor, non-drug pain management and vertical

positions during birth.

Birth was women’s

domain; her tools were her hands; her education, her experience; her focus, the

whole woman. Women assumed whatever

birth positions brought them increased comfort. Birth pain was seen to be an

unavoidable result of original sin, called the curse of Eve. Death was accepted

as a possibility; suffering was seen as inevitable (Leavitt, 1986).

The serious medical problems in

pregnancy and birth at the end of the 19th century were generally

caused by poverty and frequent close-spaced pregnancies. Remember this era was

pre-antibiotics, pre- blood transfusion, and pre-birth control.

As the latter half of the 18th century turned

into the early 19th century, it became “fashionable” in the upper to middle

class to be “delivered” at home by a male physician.

During this time there

was a dramatic increase in obstetric physicians and a decrease in midwives.

While their intentions were to make

childbirth 'safer', physicians took over the practice of midwives without any

idea of the philosophy, principles or techniques of physiological management.

The

physician’s tools were the forceps and the scissors; the focus was the birth

canal.

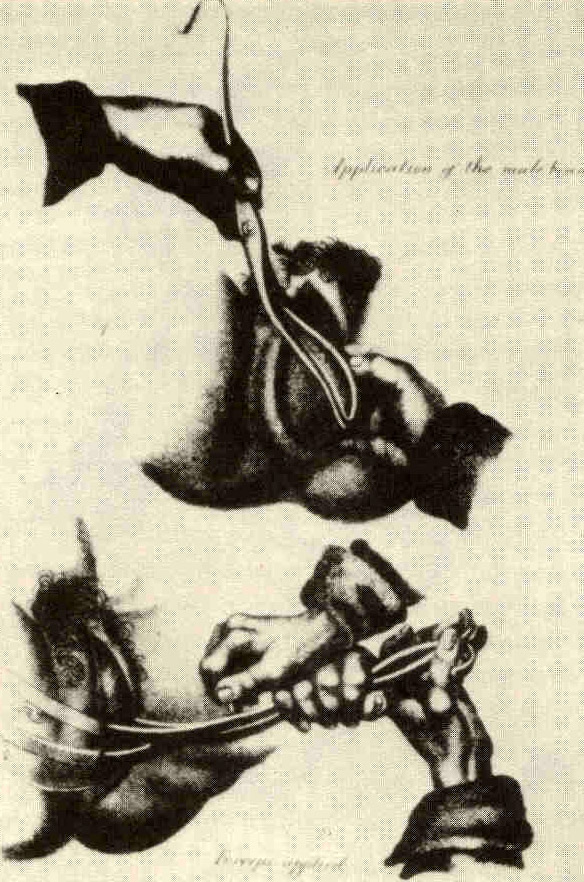

Developed in the 17th century in Europe to extract stillborn infants from

their mother’s wombs, forceps (called iron hands) became standard procedure in

the United States to extract the living infant.

Because of the horrendous

lacerations caused by the forceps, routine episiotomy had to be used to

accommodate the routine use of forceps. To ensure a painless labor and birth chloroform was

administered to render the woman unconscious.

The lithotomy position, on the back with legs elevated

strapped down and held apart control the semi-unconscious woman as well as to

facilitate the forceps, became routine.

At the end of the 19th century,

birth began to move to hospital birth as physicians continued to attempt to

improve on nature, prevent death and demystify birth (Leavitt, 1986). It was erroneously

assumed that childbirth in the controlled environment of the hospital would

eliminate the great killer of childbearing women and newborns, puerperal sepsis

or ‘childbed fever’. Nurses in the employ

of hospitals and acting under the direction and authority of physicians,

replaced the care of the midwife during the many hours of labor. When the birth

was imminent, the doctor would be called to come in and attend the “delivery”.

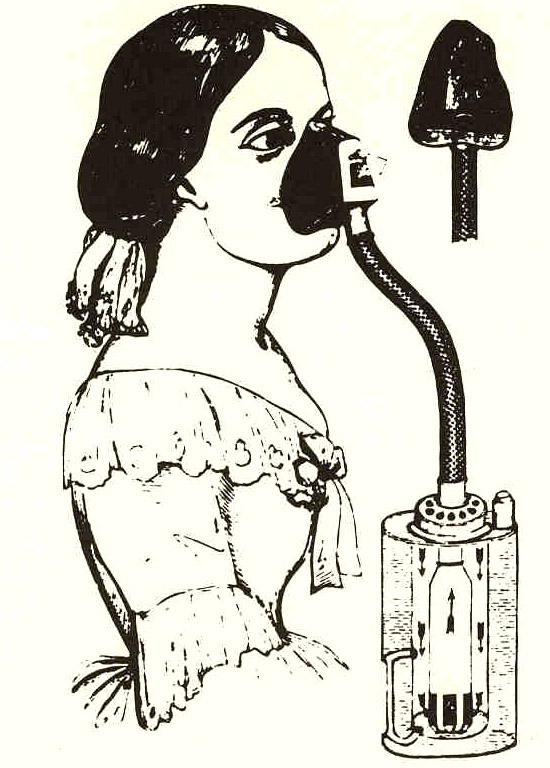

By the end of the first third of the 20th century hospital birth began to

become the norm as more middle class women embraced the new obstetrics. Twilight

sleep, a mixture of morphine, scopolamine, chloroform and ether, rendered the

woman semi to unconscious. Childbed fever became rampant due to lack of

sanitation between procedures and/or patients, and women labored in special

wards, sometimes separated only from each other by curtains (Leavitt, 1986).

By the

middle of the 20th century the “new obstetrics” was in full swing and became

the standard of care. Women received routine enemas, episiotomy, and forceps

deliveries. Arm restraints became

necessary due to the combative nature of women unexpectedly coming out of

twilight sleep, and stirrups with straps became necessary to hold the semi to

unconscious woman’s legs up and apart. Pitocin was given to speed up labor and

get the whole unpleasant experience over with, and the drugged baby needed to be

resuscitated after being pulled out (Leavitt, 1986).

By

the latter third if the 20th century hospital birth was the norm. Before 1900 5%

of women delivered in a hospital, by 1936 75% delivered in a hospital, and by

1970 99% of all women were delivered in a hospital. The perception was that

hospital birth with medical interventions was safer than a non-interventional

birth (Leavitt, 1986).

Routine medicalization and

over-treatment of healthy women has become the foremost standard for 21st

century maternity care. Today medical and surgical procedures originally

intended to treat life-threatening complications are routinely used on healthy

women with normal pregnancies, without having been proven safe or more effective

than physiological management.

- Coming to terms with the

emotional milestones to becoming a mother.

- Prenatal bonding techniques.

- Birth from the baby's point

of view

- The incredible intricacy of the hormonal regulatory mechanisms of labor

- Self-hypnosis, un-doing your response to pain. Learn to alter your response.

- Understand how to help yourself by learning ritual movements to allow your body to relax

- Breathing to enhance relaxation and the flow of hormones.

- Practical knowledge of how to move to coordinate passenger and pelvis and how to respond to contractions.

- The importance of nutrition, exercise and mind body work.

- How to take more responsibility for birth. Knowledge is power. You have the right and responsibility to come to your own informed decisions.

- Choosing a birth team

- Writing a birth plan. Take responsibility to prepare together with your health care provider with research/evidence-based information, making preparations for it to be the best experience possible.

- Physical and psychological interventions in labor and birth

- Current information about risks and benefits of medical interventions.

- Realistic risk assessment, and learn what to do in the event that risks and then to decide what to do, to decide what risk is acceptable.

- Ways to avoid unnecessary cesareans

- The safety of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC)

- Support and comfort measures for labor and birth with the comprehensive compilation of low-risk measures to prevent and treat problems in labor and birth.

- Postpartum care

- Breastfeeding baby

- Baby care and what baby

wants after birth.

When you understand what is happening in

labor you will recognize each stage as it comes and feel more confident about trying different ways of coping.

As you learn your own personal strengths and resources for labor and birth, you will learn to trust your body and the

enigma of the birth process will be rediscovered.

-

To enhance a productive labor trust your body, trust yourself and your innate ability to give birth.

-

Acknowledge the role of hormones during labor and birth.

Birth is the result of

complex, well-defined, and coordinated events, which are tightly regulated by

neurohormonal responses.

-

Come to terms with the pain of labor.

-

Resist unnecessary interventions.

-

Give birth in a setting that enhances the natural powers of labor and provide an attitude and atmosphere for their release.

-

Get good labor support.

-

Avoid induction and augmentation and epidurals unless there is a proven medical necessity.

-

Prepare to ease your baby out slowly.

-

Most of all, remember, despite your

plans and the staff's good intentions, what was planned as a low interventional

birth can turn into an involved medical procedure if last minute, unexpected

complications arise. If, for any reason, your birth experience is not what you

hoped for, it doesn't mean that you have failed. It may simply mean that forces

beyond your control have entered the picture.

Remember, birth is a powerful experience of the unknown. Not a predetermined

set of events.

There is no right way to give birth. There is only each woman’s

way.

There is no single ideal birth. There is the birth you have.

There is no

right method just the need to be integrated into the physiological,

psychological, and emotional process of the intensely private experience of

birth. This experience that is truly your own is an adventure in physical sensation and intense emotional discovery of your own inner power and strength.

Labor is an awesome treadmill of contractions and incredible intense sensations. However difficult the labor may be, you are in your own space and discover in yourself the power to give birth with the same love and passion that created your baby. As the power of the swing of contractions spreads through your body, if the power of the physicality of birth is respected, it allows you to use your body to bring forth life with strength and confidence.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality (AHRQ) 2004, Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Retrieved July 16, 2004,

from www.marchofdimes.com/peristats .

American

College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2000). News Release.

Issue: Recommendations

on Cesarean Delivery Rates.

Http://www.acog.org/from_home/publications/press_releases/nr08-09-00.htm.

American

College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (1995). Fetal Heart Rate

Patterns: Monitoring,

Interpretation, and Management

(Technical Bulletin Number

207). Washington, DC: Author.

Atrash,

H., Lawson, H., Ellerbrock, T., Rowley, D., and Koonin, L. (2000). Pregnancy Related

Mortality,

United States

CDC Surveillance Summary for Women, Infants

and Children

MMWR: p141-154

Association

of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. (2000). Position

Statement. Issue: fetal

assessment.

http://www.awhonn.org/resour/position/psresp.html.

Bricker,

L., and Luckas, M. (2000). Amniotomy alone for induction of labor.

In The Cochrane Library, Issue 4,

Oxford: Update Software.

Carroli,

G., Belizan, J., and Stamp, G. (1999). Episiotomy policies in virginal births.

In Pregnancy and Childbirth Module Issue 3, of the Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews. Oxford: Update Software

Cunningham,

F.G., MacDonald, P.C., and Grant, N.F., (Eds.). (1997).

Williams

Obstetrics

(20th edition). Stamford, CT: Appleton and Lange.

Curtin,

S.C., and Park, M.M. (1999). Trends in the attendant, place, and timing of

births,

and in the use of

obstetric interventions: United

States, 1989-97.

National

vital

statistics reports; vol. 47 no.

27. Hyattsville, Maryland: National

Center for Health Statistics.

Eason,

E., and Feldman, P. (2000). Much ado about a little cut: Is episiotomy

worthwhile? Clinical Commentary. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 95 (4),

616-8.

Eason,

E., Labrecque, M., Wells, G., and Feldman, P. (2000). Preventing perineal

trauma during childbirth: a

systematic review. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 95(3),

464-471.

Huyang,

D.Y., Usher, R.H., Kramer, M.S., Yang, H., Morin, L., and Fretts, R.C. (2000) Determinants of unexplained antepartum

fetal deaths. Obstetrics and

Gynecology,

95(2), 215-21.

Johanson, R., Newburn, M., and

Macfarlane, A. (2002).Has the medicalization of childbirth gone too

far? British Medical Journal, 324: 892 - 895.

Leavitt,

J.W. (1986). Brought to bed: Childbearing in America, 1750 to 1950. New

York:

Oxford University Press.

Maslow,

A.S., and Sweeney, A.L. (2000). Elective induction of labor as a risk factor for

cesarean delivery among low-risk women at term. Obstetrics and Gynecology.

95(6), 917-22.

National Center for Health

Statistics (NCHS) 2004, final natality data. Retrieved July 16, 2004, from

www.marchofdimes.com/peristats.

Neilson,

J.P., Crowther, C.A., Hodnett, E.D., and Hofmeyer, G.J., (Eds.). (1999).

Pregnancy and Childbirth Module, Issue 3

of the Cochrane Database of

Systematic

Reviews. Oxford: Update Software.

Putta,

L.V., Spencer, J.P., and Conemaugh, T. R. (2000). Assisted vaginal delivery

using the vacuum extractor. American Family Physician, 62(6),

1316-20.

Robinson,

J.N., Norwitz, E.R., Cohen, A.P., and Lieberman, E. (2000). Predictors of

episiotomy use of first spontaneous vaginal delivery. Obstetrics and

Gynecology 966(2), 214-8.

Thacker,

S.B., and Stroup, D.F. (2000). Continuous electronic heart rate monitoring

for

fetal assessment during labor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review. (2):

CD000063. Oxford: Update

Software.

Thacker SB, Stroup DF, Chang M. Continuous electronic heart

rate monitoring versus intermittent auscultation for assessment during labor.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD000063.

Tourangeau,

A., Carter, N., Tansil, N., McLean, A., and Downer, V. (1999). Intravenous

therapy for women in labor: implementation of a practice change. Birth,

26(1),

31-6.

Ventura,

S.J., Martin, J.A., Curtin, S.C., Menacker, F., and Hamilton, B. (2001). Births:

Final data for 1999. National Vital Statistics Report; 49(1), 1-99.

|